How to Spot a Platypus in the Wild

When and where to look

Platypus and Australian water-rats (or rakali) are most likely to be observed early in the morning or late in the evening, though they may also be active in the middle of the day.

Both platypus and water-rats occupy irrigation channels and man-made lakes and dams as well as natural lakes, creeks, rivers, backwaters and billabongs. They are generally easiest to spot in places where the water surface is fairly calm, so the ripples that are formed as the animals swim and dive stand out more strongly.

Both species occur from sea level up to alpine environments. However, platypus are not commonly seen (and never abundant) in the salty water of bays and estuaries. In contrast, water-rats make use of ocean beaches and are found on islands surrounded by sea water.

Size and appearance

Platypus are dark brown in colour, with lighter underparts and a small white patch next to each eye. Similarly, water-rat fur usually looks dark brown when the animals are wet. When water-rats are dry and seen at close range, their fur may (depending on the area) be chocolate brown, reddish brown, mouse grey or even mottled grey-brown, with underparts that vary in colour from cream to tan to golden yellow.

Both species typically float low in the water, with just the top of the head and back (and sometimes a bit of tail) visible as they swim on the surface. At a distance of more than 20 metres, even an experienced observer may find it difficult to reliably distinguish a platypus from a water-rat, especially in poor light.

A platypus seen from a distance of about 25 metres (Image 1) and a water-rat seen from a distance of about 15 metres (Image 2)

Platypus and water-rats are quite similar in size, with very large adult males of both species measuring up to about 60 centimetres in length (including the tail).

Juveniles of both species are smaller than most adults when they first enter the water, though they otherwise resemble their parents. Most juvenile platypus first emerge from nesting burrows in late January or February in Victoria and New South Wales, with Queensland juveniles emerging a few weeks earlier and Tasmanian juveniles up to around two months later. By comparison, young water-rats may be seen over a much longer period of time, from early spring to at least early autumn.

The best way to distinguish a water-rat from a platypus is to look carefully at the tail: the water-rat has a long, narrow tail with a more or less conspicuous white tip, whereas the platypus has a flat, uniformly dark, paddle-like tail.

Platypus are also very rarely seen on land, though they may occasionally rest on a log or rock, usually while grooming.

In contrast, water-rats are much more likely to be seen on land, either consuming their prey or running along the bank (Image 3).

Feeding habits and diet

The platypus’s diet mainly consists of aquatic insects such as mayfly and caddis-fly larvae, along with other invertebrates such as worms and freshwater shrimps. Although a platypus may sometimes glean prey from the water’s surface, the animals mainly find their food by diving, with around 75 feeding dives typically completed per hour.

Prey items are stored in cheek pouches and then chewed up and swallowed after a platypus returns to the surface to breathe, typically remaining visible for 10-20 seconds before again diving. In relatively still conditions the platypus will typically be surrounded by a circular pattern of ripples (Image 4). In faster flowing water, the platypus will face into the current with a V-shaped ripple pattern typically trailing behind, similar to that seen when an animal swims on the surface (Image 5).

In contrast to a platypus, a water-rat is equipped with a sharp set of teeth and front paws that are good at grasping and holding things. Therefore, although water-rats eat some of the same insects and other prey items regularly consumed by a platypus, they also dine on fish, large mussels and crabs, frogs (including cane toads) and occasionally even turtles and waterfowl such as ducks.

A water-rat normally feeds while sitting more or less out of the water – typically perching on a conveniently placed log, rock or elevated clump of reeds (Image 6). Favourite feeding spots often become densely littered with food scraps such as yabby claws or mussel shells.

In addition, a water-rat will sometimes consume its prey in deeper water, floating on its back in a very otter-like manner while using its chest and belly as a convenient dining table.

Diving patterns

A platypus diving sequence typically starts with the animal arching its back as it neatly propels itself forward and down into the water (Image 7), leaving an expanding “bull’s-eye” pattern of ripples on the surface (Image 8). Small bubbles (formed when air is squeezed from the platypus’s fur) can sometimes be seen near the centre of the ripples.

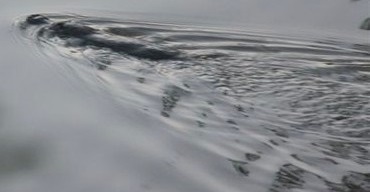

Although platypus ripples are easiest to detect in still water, they also can be visible in fairly choppy conditions (Image 9). No associated noise is heard unless the platypus has been startled, causing the animal to push itself forcefully downwards in a “splash-dive”.

A platypus will most typically remain underwater for about 20-60 seconds before popping back up to the surface, often within 10-20 metres of the point where it dived.

However, if a platypus has splash-dived due to being alarmed by a bird flying overhead or some other perceived threat, it may hide underwater for up to several minutes, conserving oxygen by wedging itself under a handy log or the roots of an undercut tree at the water’s edge. Alternatively, it may retire to a burrow or a protected location under an overhanging shrub until the danger has passed.

A water-rat diving sequence also starts with the animal arching its back and forcing itself forward and down into the water, often exposing the white tip of the tail as it does so (Image 10). The ripples formed when a water-rat dives (Image 11) are generally less well defined than those created by a platypus.

Water-rats typically stay underwater for less than a minute and often emerge on the surface relatively far from where they dived, reflecting the fact that they have been chasing fish or other prey underwater.

Swimming on the surface

A platypus that wants to swim directly and rapidly from one site to another (for example, to return to a burrow to rest or to chase another platypus) will travel mainly on the surface in order to be able to breathe and paddle at the same time.

This type of movement typically results in a long, narrow wake (Image 12), often viewed from a distance as a distinctive silvery streak.

Platypus use only their front legs to propel themselves in the water, resulting in quite a strong bow wave and relatively narrow trailing wake (Image 13). By comparison, water-rats mainly swim using their hind legs, typically producing a wider trailing wake (Image 14).

The platypus has been calculated to swim most efficiently at a speed of about 1.4 kilometres per hour in an experimental setting. Animals in the wild have been found to travel upstream and downstream along a medium-sized river at speeds of up to 1.6 kilometres per hour and 2.4 kilometres per hour, respectively.

Though many platypus videos can be seen on the internet, most are fairly low quality. Four reasonably good examples that collectively show animals swimming, floating and diving (and also grooming and scrambling through shallow water) can be found at:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gp-JNLEJq_w

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bayGLS3dZyo

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rOgS6ZojDoc

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Qe2OORSMq0

Some videos showing how water-rats swim and dive (and groom their fur when out of the water) can be found at:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_G9_tKKyS5g

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=usqjoOvnlV0

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hV7YkRgOv5w

Other behaviour

When resting on the water surface, a platypus may spend quite a lot of time scratching or combing its fur with a hind foot and can often look quite contorted (or ecstatic) while involved in this activity. (Image 15)

Water-rats may occasionally give themselves a quick scratch while in the water but prefer to carry out most grooming activities on land.

Some other animals that can be mistaken for a platypus or water-rat

It is possible to confuse diving birds (such as ducks, grebes, cormorants and darters) with both the platypus and water-rat. This is especially true of musk ducks (Biziura lobata) - large, dark birds that often swim alone and produce a platypus-like pattern of ripples when they dive (Image 16). Particularly in autumn, a male musk duck will sometimes swim with his head and neck stretched out straight in front of him near the water surface, producing a very platypus-like outline.

To distinguish waterbirds from platypus and water-rats, keep in mind that the silhouette of a platypus or water-rat is much flatter than that of even relatively small birds such as grebes and coots. If the profile of a swimming animal projects well above the water surface, it is unlikely to be that of a platypus or water-rat.

Turtles and some large freshwater fish (such as carp, eels and freshwater catfish) can sometimes be mistaken for a platypus or water-rat, particularly if glimpsed for only a few seconds in dim light. Carp in particular may spend long periods of time with their backs well out of the water as they feed near the shoreline. However, the identity of turtles and fish usually becomes quite obvious with more careful observation.